Pictorialists were arguably the first artists to use photography to create images drawn from the imagination. These photographers literally paved the way for all photographers after them to be accepted and recognized as artists.

Now for the bad news. I don’t believe very many photographers today embrace the concept of creating new work from their imagination. It is easily spotted because they cannot describe their work’s purpose through a clearly articulated artist statement and narrative.

Pictorialism was a photography movement that thrived for three decades and aimed to elevate photography to the status of fine arts. The movement is known for producing some of the most striking and artistic photographs in the genre’s history, characterized by their sumptuous, beautifully colored landscapes, evocative portraits, and poetic allegories.

Pictorialists aimed to create photographs that resembled paintings, watercolors, or drawings by using techniques such as soft focus, special photographic papers, and hand-applied colors.

Share your email address below and you will get an update when I publish new articles.

Note: you will need to confirm your subscription. If you don’t see a new email, check your SPAM or Junk folder.

The term “Pictorialism” stems from “picture-ism” and was associated with the Aesthetic Movement in art. It was loosely linked with movements like Art Nouveau, Romanticism, Symbolism, and early modern art. Pictorialists used their medium to convey artistic impressions, akin to the self-expression found in Impressionist paintings, thus the term “Photographic Impressionism” is also associated with Pictorialism.

Pictorialist photographs are often mistaken for traditional art forms because of their artistic qualities and the creators’ desire to establish a new and distinctly modern world of visual expression. The Pictorialists were some of the first artists to use photography to create images drawn from the imagination, showing a nostalgic but affectionate attitude towards photography that has driven artistic practice ever since.

Their techniques involved the use of soft-focus lenses, manipulation of the photographic print surface by applying emulsions, and using colors from subtle earth and vivid hyper-real hues. They often used hand-made photographic prints, and methods similar to those used in painting, which allowed them to manipulate the appearance of their images creatively. Pictorialists also favored certain papers and chemicals that let them achieve the desired effects.

Pictorialism, however, faced criticism for its perceived elitism, despite its democratic rhetoric. It was seen as a way for photographers to distinguish themselves from the mass of amateur photographers enabled by new technologies like Kodak’s legendary roll-film camera.

The movement declined when the pictorialists’ sentimental themes and methods fell out of fashion after World War I. A new preference for sharp-focus realism emerged, exemplified by groups like Germany’s Neue Sachlichkeit and California’s Group f/64. Yet, Pictorialism’s impact on photography’s claim for artistic legitimacy and its expansive approach to image manipulation continued to influence the field.

Why I am I Pictorialist

In the realm of photography, the medium’s evolution has seen a shift from the soft, ethereal qualities of 19th-century Pictorialism to the sharp, precise workflows of modern digital photography. However, in the context of my project, the deliberate choice to employ Pictorialist methods is not merely a nod to historical techniques but a vital component in conveying the depth of my emotions and the narrative of my journey.

Emotional Resonance and Authenticity: The Pictorialist approach, with its emphasis on mood and atmosphere, aligns perfectly with the intent to capture more than just the physical appearance of trees. The soft focus and dreamlike quality of images produced through methods like Calotype paper negatives and Kallitype or toned Cyanotype processes allow for a visual representation of memory and emotion that is nuanced and deeply felt. These techniques enable the photographs to transcend being mere records of landscapes, instead becoming expressions of longing, remembrance, and the complex layers of grief.

Engagement and Intimacy: The hands-on nature of 19th-century photographic processes demands a level of engagement and intimacy with the material that modern techniques often lack. Each step, from preparing the paper negatives to the final printing, requires a mindfulness and dedication that mirrors the slow, reflective journey of healing. This meditative practice allows for a deeper connection with each image, ensuring that every photograph is not just a picture but a personal testament to the journey of grief and recovery.

Imperfections and Individuality: The Pictorialist methods are inherently imperfect and unpredictable. The unique variations and anomalies that arise in each print reflect the individuality of my experience. Just as no two grief journeys are the same, each photograph carries its own set of idiosyncrasies, making it a unique artifact that speaks to the personal nature of the project. These imperfections are not flaws but rather visual representations of the raw, unfiltered reality of grief—its unpredictability, its rough edges, and the way it can alter one’s perception of the world.

Contrast to Modern Sharpness: In contrast to the sharp, clinical precision of modern digital photography, the soft, sometimes ambiguous, imagery of Pictorialism better encapsulates the elusive nature of memory and emotion. The dreamlike quality of the images invites viewers to engage with them not just visually but emotionally, offering a space for reflection and connection that sharp, detailed photos might not.

In conclusion, the use of 19th-century Pictorialist methods is not just a stylistic choice but a fundamental component of the project’s emotional and narrative depth. It allows for a more authentic, intimate portrayal of grief and memory, inviting viewers to not only see the world through my eyes but to feel it through my heart. As I continue to photograph trees and explore this deeply personal landscape, the Pictorialist approach remains a vital tool in my quest to understand and articulate the journey of loss and healing.

Famous Pictorialist Photographers

Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) – “The Hand of Man” (1902), born in Hoboken, New Jersey, and is regarded as an instrumental figure in the acceptance of photography as a serious art form. He became obsessed with photography in his youth and remained in Germany to study the subject deeply after his parents returned to America. Stieglitz was known for his high standards and the Photo-Secession group he formed, challenging the status quo of art. His gallery “291” introduced many avant-garde European artists to the U.S. He was also known for his photographs of Georgia O’Keeffe, who became his wife and muse. [more info and photos at Library of Congress]

As proprietor of the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession and editor of the photographic journals Camera Notes and Camera Work, Stieglitz was a major force in the promotion and elevation of photography as a fine art in America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. His own photographs had an equally revolutionary impact on the advancement of the medium.

The Hand of Man was first published in January 1903 in the inaugural issue of Camera Work. With this image of a lone locomotive chugging through the train yards of Long Island City, Stieglitz showed that a gritty urban landscape could have an atmospheric beauty and a symbolic value as potent as those of an unspoiled natural landscape. The title alludes to this modern transformation of the landscape and also perhaps to photography itself as a mechanical process. Stieglitz believed that a mechanical instrument such as the camera could be transformed into a tool for creating art when guided by the hand and sensibility of an artist.

Art Overview and Interpretation of Alfred Stieglitz’s “The Hand of Man”

Alfred Stieglitz’s “The Hand of Man” is a seminal photograph taken in 1902, depicting the raw power and industrial might that characterized the early 20th century. This image features a locomotive billowing thick smoke as it moves along the railyards, with an intricate network of tracks converging in the foreground and industrial buildings looming in the distance.

Interpretation

To interpret “The Hand of Man,” one must consider the context of the era and the symbolic resonance of the locomotive. It embodies the Industrial Revolution’s impact, showcasing human achievement and the transformation of the natural landscape. The train, a triumph of engineering, represents progress, while the smoke may suggest the environmental and social costs of industrialization. The converging lines of the rails draw the viewer’s eye into the photograph, signifying the many paths of progress and their intersection at the dawn of the new century.

Little-Known Facts

One of the lesser-known aspects of “The Hand of Man” is that Stieglitz captured this image from the back of the New York Central Railroad’s 61st Street Yard. The print is noted for its range of tones, achieved through Stieglitz’s mastery of photogravure, a process that added a painterly effect to the photograph. This technique aligned with the Pictorialist movement’s aesthetic, seeking to emulate the tonalities and textures of painting.

Pictorialism and Photography as Fine Art

Pictorialism was a pivotal movement that helped elevate photography to the status of fine art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Pictorialists like Stieglitz believed that photography should be more than a mere mechanical reproduction of reality; it should express the artist’s vision and emotional response to the subject. By employing techniques such as soft focus, special filters, and unique printing processes, Pictorialists created images that were more personal, subjective, and expressive. “The Hand of Man” is a prime example of Pictorialism’s influence, where the aesthetic choices in composition, lighting, and printing contribute to an artistic interpretation rather than a straightforward record of the scene.

Stieglitz’s work, including “The Hand of Man,” played a crucial role in this movement. His efforts to showcase photography as an art form were further amplified through his work as an editor for “Camera Work,” a periodical dedicated to photography as a fine art, and his role in establishing the Photo-Secession group, which championed Pictorialism and the creative potential of photography.

Conclusion

“The Hand of Man” stands as a testament to the transformative power of the Pictorialist movement and Alfred Stieglitz’s vision in shaping the course of photographic art. Its rich tonality, evocative composition, and the underlying themes of progress and its repercussions continue to captivate audiences, serving as a powerful historical record and a work of art that bridges the gap between photography and painting. Through images like this, Pictorialism affirmed photography’s place in the pantheon of fine arts, allowing photographers to be recognized as true artists.

Edward Steichen (1879–1973) – “Flatiron Building” (1904), born Éduard Jean Steichen in Luxembourg, emigrated to the United States with his family at a young age. A painter by training, he was a key figure in transforming photography into an art form and became the most frequently featured photographer in Alfred Stieglitz’s “Camera Work.” His contributions to fashion photography are seminal, including his famous images for “Art et Décoration” in 1911. Steichen was also a war documentarian, winning an Academy Award for “The Fighting Lady.” Later, he served as the Director of Photography at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and curated “The Family of Man” exhibition, which was seen by millions and recognized by UNESCO. [more info and photos]

Your essay on Edward Steichen’s famous photograph of the Flatiron Building provides a detailed description of both the building and the photograph. Here’s a revised and expanded version for enhanced clarity and to provide additional information about Pictorialism:

The Flatiron Building: A Pictorial Masterpiece by Edward Steichen

The Flatiron Building, originally known as the Fuller Building, is an iconic structure located at 175 Fifth Avenue, New York. Positioned on a triangular block bordered by Fifth Avenue, Broadway, and East 22nd Street, this Renaissance-style building, completed in 1902, is renowned for its unique shape that tapers at 23rd Street. This tapering creates a wind tunnel effect, which infamously lifts skirts, leading to the coining of the term “23 skidoo” by policemen clearing ogling crowds.

Photographic Legacy of Edward Steichen

Edward Steichen, initially trained as a painter, played a pivotal role in elevating photography to the status of fine art. In 1903, he captured the Flatiron Building in a way that emphasized its novel architectural style. Stationing himself on the west side of Madison Square Park during dusk in winter, Steichen managed to encapsulate the building’s imposing presence and moody ambiance. He created three distinct prints of this photograph in 1904, 1905, and 1909, employing a technique that involved applying pigment suspended in gum bichromate over a platinum print, resulting in blue, tan, and orange-colored versions.

Pictorialism and Its Influence

Pictorialism, the movement to which Steichen contributed significantly, sought to validate photography as a legitimate art form. This movement emphasized beauty, tonality, and composition over the mere documentation of reality. Steichen’s Flatiron Building photograph is a quintessential example of Pictorialism, with its soft focus, atmospheric effects, and hand-applied color, all contributing to an artistic and painterly quality.

Connections and Collaborations

Steichen’s mentor, Alfred Stieglitz, captured the Flatiron a year earlier in a manner influenced by Japanese woodcuts, showcasing the building amidst a snowy landscape and a Y-branched tree. Steichen’s photograph is often seen as a conversational piece in response to Stieglitz’s work. Together, they founded the 291 Gallery in 1905, a space that became a hub for avant-garde art. Unfortunately, the building that housed the gallery and Steichen’s top-floor studio has since been demolished.

Interpreting the Photograph

Steichen’s Flatiron image is more than a mere representation; it’s a study in contrasts and mood. The lively composition leads the eye from the tree branches to the wet street below, creating a dynamic yet still scene that captures the essence of the moment. The photograph reflects the complex interplay of light, from the artificial glow of street lamps to the natural twilight, imbuing the scene with a romantic yet melancholic atmosphere. Figures and carriage drivers, almost ghostly in appearance, move slowly through the elements, reflecting the struggles and pace of early 20th-century life.

Legacy and Influence

In 1933, Stieglitz donated all three of Steichen’s Flatiron prints to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, ensuring their preservation and public accessibility. These prints, measuring 8 13/16 x 15 1/8 inches, continue to inspire and intrigue viewers with their pictorial beauty and historical significance.

Conclusion

Edward Steichen’s photograph of the Flatiron Building is not just an image; it’s a rich narrative woven into the fabric of New York’s architectural and artistic history. As an exemplar of Pictorialism, it goes beyond capturing a moment in time, offering a profound commentary on the nature of art, light, and the ever-changing urban landscape. As viewers, we are invited not just to see but to feel the photograph, to immerse ourselves in its moody, evocative atmosphere, and to appreciate the nuanced interplay of light, texture, and emotion that Steichen so masterfully captured.

Clarence H. White (1871–1925) – “Morning” (1908), “Nude” (1908), and “Torso” (1907, with Alfred Stieglitz), born in West Carlisle, Ohio, was a self-taught American photographer and teacher. After being inspired by the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, White rapidly gained international recognition for his pictorial work that portrayed the essence of early twentieth-century America. He was a founding member of the Photo-Secession movement and a close collaborator with Alfred Stieglitz. In 1914, he founded the Clarence H. White School of Photography in New York, the first institution to teach photography as an art form. White’s dedication to teaching later overshadowed his own work, and he passed away in 1925 while instructing students in Mexico City. [more info and photos]

Gertrude Käsebier (1852–1934) – “Blessed Art Thou Among Women” (1899), was an influential American photographer known for her evocative images of motherhood, powerful portraits of Native Americans, and for promoting photography as a career for women. Born in Des Moines, Iowa, she moved to New York after her father’s death and later attended the Pratt Institute of Art and Design. Her marriage, though unhappy, did not hinder her pursuit of art, and she became a professional photographer in 1895. Käsebier was a founding member of the Photo-Secession and was praised by Alfred Stieglitz in “Camera Work.” Her portraits emphasized the individuality of her subjects over their attire or cultural background. Despite personal challenges, she continued to exhibit her work and influence the field of photography. In 1929, Käsebier retired and was later recognized posthumously for her contributions to the art of photography. [more info and photos]

Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882–1966) – “Spiderwebs” (1908) was an American photographer who played a significant role in the development of American pictorialism. Born in Boston, he moved to London in the early 1900s, where he became known for his portraits of famous literary and artistic figures. Coburn’s work was characterized by its soft focus and often abstract qualities, with “Spiderwebs” showcasing his experimentation with unconventional subjects and compositions. He later delved into abstract photography, pioneering a technique he called vortographs. [more info and photos]

Annie Brigman (1869–1950) – “Soul of the Blasted Pine” (1908) was an American photographer, one of the original members of the Photo-Secession movement led by Alfred Stieglitz. Known for her ethereal and symbolic images that often featured nude female figures in natural landscapes, Brigman’s work, including “Soul of the Blasted Pine,” was revolutionary for its depiction of the female form and its connection to nature. She often used herself as a model, photographing in remote locations to capture the raw and mystical interaction between the human figure and the natural world. [more info and photos]

Paul Haviland (1880–1950) – “Doris Keane” (1912) a French-American photographer, was a prominent figure in the early 20th-century pictorialist movement. His photograph “Doris Keane” illustrates his skill in portrait photography. Haviland was also known for his involvement with the Photo-Secession group and his contributions to the advancement of photography as a fine art. He was a frequent collaborator with Alfred Stieglitz and contributed to the influential publication “Camera Work.” [more info and photos]

Robert Demachy (1859–1936) – “Struggle” (1904), a leading figure in French pictorial photography, Robert Demachy was known for his expressive and heavily manipulated images. “Struggle,” one of his most famous works, exemplifies his use of the gum bichromate process, which allowed for painterly manipulation of the photographic image. His work often focused on the human figure, dance, and movement, showcasing a blend of artistic sensibility and technical skill. [more info and photos]

Constant Puyo (1857–1933) – “Sommeil” (1897), “Montmartre” (1906) was a central figure in French pictorialism. His photographs, including “Sommeil” and “Montmartre,” often depicted ethereal, dreamlike scenes, showcasing his fascination with soft focus and natural light. Puyo’s work was influential in establishing photography as a form of artistic expression in France. [more info and photos]

F. Holland Day (1864–1933) – “Ebony and Ivory” (circa 1897) was an American photographer and publisher who was a key figure in the pictorialist movement. Known for his controversial and often religiously themed works, Day’s “Ebony and Ivory” is a testament to his artistic vision and his interest in exploring racial and social themes through photography. He was also a mentor and promoter of several younger photographers and artists. [more info and photos]

Adolph de Meyer (1868–1949) – “Marchesa Casati” (1912) a German-born photographer, was known for his elegant and stylized portraits of high society figures, including the famous “Marchesa Casati.” He worked primarily in Paris and New York and is often credited with being one of the first fashion photographers. His work was characterized by a unique blend of naturalism and theatricality. [more info and photos]

Joseph Keiley (1869–1914) – “Lenore” (1907) was a close associate of Alfred Stieglitz and a regular contributor to “Camera Work.” His photograph “Lenore” reflects his interest in soft-focus techniques and his dedication to elevating photography to the status of fine art. Keiley was known for his portraits and for advocating the pictorialist style. [more info and photos]

Julia Margaret Cameron (1815–1879) – was a British photographer who became famous for her powerful and intimate portraits of Victorian celebrities and for her illustrative images depicting characters from mythology, Christianity, and literature. She is credited with producing some of the first close-ups in the history of photography, and her work is celebrated for its pioneering approach to portrait photography.

She is known for her soft-focus close-ups of famous Victorian men and women and for illustrative images depicting characters from mythology, Christianity, and literature. She has been credited with producing the first close-ups in the medium’s history. [more info and photos]

William Henry Peach Robinson (1830–1901) – His most famous composite picture is “Fading Away” (1858), which was popular and fashionably morbid.

William Henry Peach Robinson was a prominent English photographer and one of the most influential figures in Victorian art photography. Born in Ludlow, Shropshire, Robinson initially pursued a career in painting before turning to photography, where he became a master of the early technique of combination printing.

His most famous work, “Fading Away” (1858), is a remarkable example of this technique. It was a composite image made from several negatives, which allowed Robinson to create a narrative scene that depicted a young girl dying of consumption, surrounded by her family. This work stirred controversy for its staged portrayal of death, but it also demonstrated Robinson’s commitment to photography as a form of artistic expression, not just a means of documentation.

Robinson was a strong advocate for photography as an art form, and his ideas were instrumental in the rise of the Pictorialist movement. He wrote several influential books on photography, including “Pictorial Effect in Photography” (1869), in which he argued for the potential of photography to compete with traditional art forms.

Throughout his career, Robinson continued to experiment with photographic techniques and compositions, striving to bridge the gap between photography and painting. His legacy is marked by his innovative approach to photographic composition and storytelling, as well as his role in shaping the early artistic direction of photography.

These photographers were pioneers in their field, blending artistic vision with photographic technique to create works that were both innovative and expressive of their time. [more info and photos]

Share your email address below and you will get an update when I publish new articles.

Note: you will need to confirm your subscription. If you don’t see a new email, check your SPAM or Junk folder.

Pictorial Whispers – More Than Art

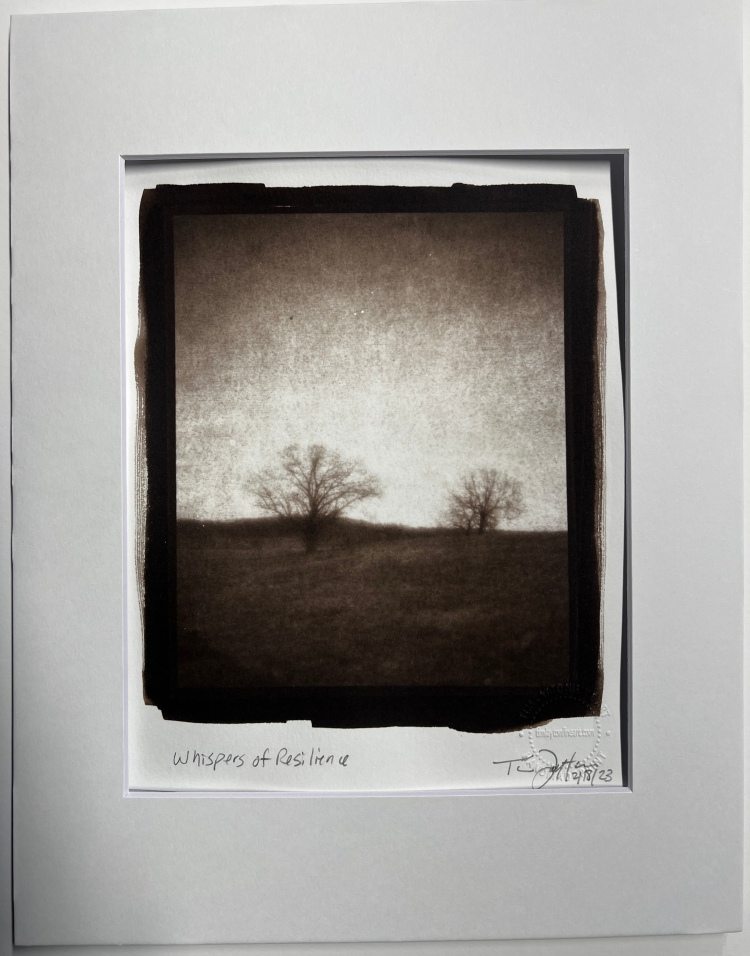

Each handmade print in the Pictorial Whispers series is a captured echo of love and sorrow, where trees stand as poignant testaments to the memory of my beloved daughter, affectionately known as Peanut.

Through the ethereal embrace of Pictorialism, these stoic beings are transformed into guardians of her legacy, their roots entwined with the depths of my emotions.

This work transcends the realm of visual art; it is a sacred process, a conduit through which I navigate the labyrinth of heartache.

Embracing the 1850s negative process of collodion glass plates, with its inherent imperfections and richness, I have found a profound connection to Abby. The physicality of this medium, with its labor-intensive demands and unique aesthetic, mirrors the intricate complexities of my emotional state.

The complex and constantly evolving chemistry process and the handmade aspect of the workflow all contribute to a deeply personal and expressive narrative. Each image I compose is a stanza of an ongoing dialogue with absence and memory, where the chemical nature of the collodion process adds an almost otherworldly character to the images, blurring the lines between sharp reality and the soft edges of remembrance.

In my handmade photographs, trees are more than mere subjects; they are characters imbued with human emotions, standing as silent witnesses to the internal storm of my grief. They echo my solitude, resonate with my sadness, and yet stand resilient, a reflection of the strength I muster each day.

The dance of light and shadow amidst these arboreal forms is akin to my brushstrokes on this canvas of loss. This interplay becomes my visual language, a means to articulate the indescribable path of mourning and eventual healing. In creating my handmade wet plate collodion negatives and platinum-toned Kallitype contact prints, I find a semblance of peace, a fleeting respite from the relentless grip of emotional pain.

My artistic quest with Pictorial Whispers is to forge an enduring, mystical, and deeply personal collection. In this pursuit, I maintain a profound spiritual bond with Abby, channeling the flux of my emotions—grief, gratitude, and love—into the stillness of the natural world.

Each handmade print is a physical manifestation of my experiences, a testament to the enduring impact of Abby’s presence in my life. Through this process, I hope to offer a visual homage to her memory, crafting expressive artwork that are as singular and special as the moments we shared. Abby’s spirit, her joy, and the name Peanut are forever intertwined with the essence of the trees that I photograph. They are my silent and steadfast companions on a path through the unknown terrain of heartache and recovery.

Share your email address below and you will get an update when I publish new articles.

Note: you will need to confirm your subscription. If you don’t see a new email, check your SPAM or Junk folder.

EXPLORE & CONNECT

I encourage you to go beyond the surface and explore my artist statements for Pictorial Whispers and America’s Grist Mills. Every technical and creative choice I make aligns with my projects’ narrative.

To receive updates about exhibitions, new articles, and the latest information about my 19th century analog photography projects, enter your email in the form below and join me in celebrating the beauty and power of visual art.